I found out on Saturday morning that my old gymnastics coach died late on Friday. I was devastated. I hadn’t seen him in probably 8 years, and he hasn’t been my coach in a decade and a half. But my sadness felt urgent and all consuming instead of distant. I didn’t talk about it to anyone except my family (who knew him, too) because I couldn’t talk about it without crying, and because it felt somehow too personal, and mostly because I felt like I had no right to that level of sadness. I spent most of the day alone, just remembering, and when I sat down to write a little commemorative post, I realized I had a lot more I wanted to say.

I was a kind of impossible kid. I was so painfully shy that I practically couldn’t function around anyone who wasn’t immediate family, and my poor mom had no idea what to do to help. My sister did dance and softball — the regular things all the kids did in my hometown. My mom tried to put me in softball when I was 5 or 6. I spent a miserable season hiding from the ball in the outfield and running in the opposite direction if it flew my way. Then she tried dance class, and then acrobatics, both of which entailed me sitting in her lap for most of each class and refusing to participate in the recitals. Interacting with an instructor I didn’t know was scary, and the thought of an audience watching me was petrifying. And then when I was 6 years old, I watched the 1996 women’s gymnastics team win Olympic gold in Atlanta, and I told my mom that’s it. That’s what I want to do.

Desperate to prevent me from being a mute hermit, she enrolled me at the only gym in my town, which was a great place for cheerleading and tumbling, but also had gymnastics equipment from the 70s and hadn’t had a competitive gymnastics team in over a decade. I wanted to compete, but we didn’t know of any alternatives, so I was content to be there and learn as many new tricks as possible (without talking to anyone). Months later I was with my mom in Slidell and saw the silhouettes of gymnasts painted in the windows of a strip-mall storefront. I knew there was probably no way I could go to that gym—it was at least an hour from my house, and even then I knew it would be far more expensive than the gym in my town—but I begged her to at least let us go look inside.

A week later we were back for my first class. I don’t know if I’d ever been so excited for anything. Because of a mix-up by a substitute manager who was filling in for the day, I was accidentally placed in the team class instead of the recreational class—something that probably wasn’t supposed to happen for months. There were two male coaches in the gym—a man named Alex who coached the lower levels and an older man named Victor who coached the older girls (who all looked like Olympians to me). I was both terrified by and in awe of Victor (and his wife, Tamila). I sensed he was legendary before I even knew the details —that he and Tamila were the Soviet coaches of the ’92 Olympic all-around champion, that her medal ceremony was the first time the Ukrainian flag had ever flown at an Olympic Games (the Soviet Union had just fallen), and that they’d immigrated to America just a few years before I walked in that gym (I’m not sure I’d ever heard a foreign accent in person before I heard theirs). To my 7-year-old self, he was superhuman, the embodiment of all my unattainable dreams.

He and Alex watched me during that first practice. They took me aside and asked me to show them the skills I knew. They spoke quietly in Russian to each other. And by the end of that practice, Victor introduced himself to my mom and said they wanted to invite me to join the team. My mom knew there was no chance she could refuse because for the first time in my life, I wasn’t hiding in a corner afraid for anyone to watch me. There haven’t been many single moments in my life I can point to as life-changing. But that was one.

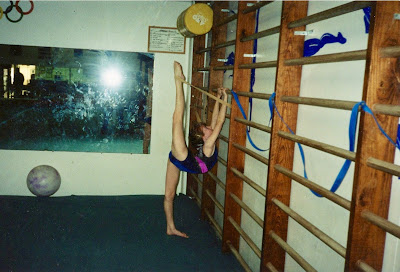

Victor and Tamila became my coaches after my first competition season, and they remained my coaches for the next 5 years. That meant that I spent more time with them and my teammates than I did with anyone outside of my immediate family. We moved into a smaller, old gym after the lease was up on the original one. None of us minded what it looked like. Their daughter, Tetyana, immigrated soon after and became our choreographer and coach, as well (completing the best team of coaches I ever had). Then came Tetyana’s husband and daughter, who became my childhood friend. What started as two practices a week quickly became 4 and 5 practices a week for 3 or 4 hours a day, and 8 hour days 5 days a week during the summer. It’s sounds cliche when athletes say their coaches and teammates are like second families. But it’s also true.

In the gym, the shyness that was so debilitating in every other area of my life melted away. I was hungry for as much as I could get and, to the shock of everyone who’d ever known me, I was thrilled at any opportunity to perform in front of people. (And let me be clear—I was not the best. I was nowhere close to the best. I just loved it that much.) In the gym, Victor was my number one supporter. He saw something in me that I couldn’t see in myself, and he never let me forget it.

Bars was the bane of my existence. I hated the event. I spent agonizing hours in practice and in private lessons trying to get my bar skills up to speed. I was too horrified to try a giant, but Victor told me 400 times that my form was perfect so that I still felt confident enough to keep trying.

When I got my first rip on my hand from bars, he cut the bloody flap of skin off my palm with nail scissors, placed it in the middle of my palm and closed both of his hands over it. Be proud of this, he said.

I remember how secretly proud I always felt when we found out the competition order he and Tamila had chosen. Coaches generally strategize when choosing the order their team members compete. The expected high score goes last, and then essentially you work backward from there. But your first competitor should be your steadiest one, the one who you can trust to handle the competition nerves, the one who will set the standard for everyone else. I would never have chosen to go first myself. But there was no better feeling than when they chose me to go first on 2 or 3 events every competition. (Except for maybe the feeling when sometimes I was picked to go last.) There is perhaps no better way to build someone’s self-confidence than to show, for an audience to see, that you have confidence in them.

When I picture Victor during those years, I remember so clearly how youthful he was. He must have been in his 60s at the time, but everything about him seemed young. I remember how he would catch us in mid-air when we practiced bar dismounts. (Was there anyone else in my life I would have trusted to do that?) He was a small man, but spotting anyone seemed effortless for him. He had the body of a man half his age. He used to swim for miles each morning in the pool at his apartment complex (where he’d bring us to swim twice a week in the summers). It was so important to him that we balance the hard work we did with fun. During our lunch break in the summers, he’d bring everyone to the floor for dodge ball games. (My years running from softballs paid off.) He was soft-spoken and loved to laugh. I don’t recall ever hearing him raise his voice.

One of my favorite memories is when I did a kip for the first time on the low bar. (If you were never a gymnast and you look this skill up on Youtube, you will not be impressed. But if you were ever a gymnast, perhaps you understand the agony of trying and failing for actual years to get that stupid skill.) It was the Louisiana State Meet at LSU, the last competition of the year. For every competition that year leading up to state, I’d tried the kip, failed, and done it again with him helping me (yes, a huge deduction, but I had to compete the skill, and my score was going to be a disaster no matter what). Except that time, I did it. I could hear my gym’s section of the audience cheering as if I’d just won Olympic gold, and I remember seeing out of the corner of my eye from the high bar that Victor was jumping and running in circles, arms raised, dancing like a maniac. For the entire rest of the routine he danced with the whole crowd watching. He apologized to the judges afterward, then bear-hugged me with tears in his eyes and told me that he hadn’t been this excited when Tatiana Gutsu won the Olympic gold. “I didn’t cry then,” he told me, “but I cry now.” Of course I wasn’t sure that I believe him. But then again…

I was 12 when Victor and Tamila moved away for a coaching job in California. It was one of the saddest goodbyes I’d ever had to say, and I still remember crying as I walked out of that gym with my teammates for the last time that night in December. I went to two more gyms after Victor left. I never stopped loving gymnastics. (I still haven’t stopped loving gymnastics.) But no other coach ever made me feel as confident or sure as he made me feel. 14 years later, it’s still hard to talk about why I walked away from competitive gymnastics. The simplest thing to say is that I felt like I’d come to the point of picking a route forward. The gymnastics route where there was a single goal (full-paid college scholarship to a college with a good gymnastics program) and no room for error, or the academic one where options felt endless. I couldn’t do both. And I guess something else Victor taught me was that sometimes you have to leave something you love to pursue a different dream.

In college, I found out that Victor and Tamila had moved back the area and were coaching at one of my former gyms in Mandeville. I remember how hard my heart was beating when I went to visit during a holiday break. I hadn’t contacted them beforehand, and they hadn’t seen me in nearly a decade. Would they even recognize me? When they saw me, they stopped class and pulled me onto the floor to introduce me to the girls’ team—all of them the age I was when they were my coaches. Victor convinced me to warm up with the class, and then he came with me when I tried to make my body remember how to tumble on the tumble track. It was the best gift I could have asked for. They retired not long after that and then moved away with the rest of their family. I’m so grateful for seeing him that last time.

The actual skills Victor taught me were secondary to the ways he changed me as a person. Victor was one of the most accepting people I’ve ever known. Everyone, no matter their background, skill level, age, or size, was welcome in his gym. He taught me quiet confidence and pride and how the things we work hardest for should always be things we love. He taught me about perseverance, discipline, and most everything that has helped me have any degree of success in anything I’ve done since.

There’s been so, so much in the news for the past couple of years about USA Gymnastics. Child abuse and molestation and eating disorders and permanent emotional damage. It’s hard to watch as more and more people are sharing more and more of these stories, and it’s heartbreaking to see the world learning to affiliate the sport with abuse like this. It’s hard to know that parents have not allowed their little girls to start or continue gymnastics because they associate it with these cases. I wish I could tell them that there’s an awful lot wrong with elite gymnastics and the national team setup, and that there are a lot of terrible people affiliated with this sport, and those are rightful things to be wary of. But I also want to tell them that’s not all the sport is. Let me tell you about my childhood gym and my coach. This is what gymnastics is supposed to be. This is what a coach is supposed to be.

I’m thinking of Tamila, Tetyana, Lana, and their family tonight, and I’m so grateful for these memories of Victor. I’m lucky to have known him.