We caught the earliest train out of Strasbourg before 5:00am. It took us straight to Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris through a high-speed tunnel that I didn’t know existed. I cried in the airport, both because I was terrified to fly and because I was sad for my trip to end.

One thing I heard over and over again from other travelers on this trip was about backpacker’s fatigue. I’d prepared myself for feeling it, too—an eventual exhaustion from a fast-paced lifestyle without enough rest and where places lose their allure because you’ve seen too many back-to-back. So many people I met told me they were thrilled to be going home. After a month, they were ready for their own bed. After 3 months, they were counting down the days until their return flights. I kept waiting for it to hit me. But it never did. Even when I had Covid. Even when I was sick with a stomach bug. Even when I was afraid to head into Romania because nuclear tensions were so high in neighboring Ukraine. I never felt done. I still don’t feel done, even now, even a year later. I think maybe there’s no amount of travel that would make me feel like that was enough.

I’d only ever flown on overseas flights alone, and having my mom with me this time made it easier. After more than 10 years of trying to convince her to make the journey to Europe with me, it felt unreal that it actually happened. As much as we’d worried about the logistics of the trip for her because of her arthritis and neuropathy, she never missed a thing, which I attribute largely to joy and adrenaline. What a gift it is to be able to surprise yourself. Still today as I’m writing this a year later, it feels like I dreamed it.

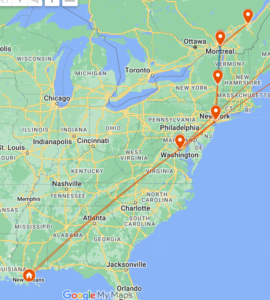

We landed in Washington, D.C.—the same airport where I’d had a panic attack and nearly refused to get on the plane (for the second time) 5 months prior. You would think that a totally uneventful 8-hour flight across the Atlantic would make a quick 2-hour flight the rest of the way home feel easy, but there were so many emotions blocking my ability to deal with the anxiety. It was dark and there was bad weather between D.C. and home, and I knew the flight would be turbulent. I am not a person who gets less nervous once the plane successfully takes off—the expanse of time in the air leaves me increasingly panicked, and after the 8-hour flight, I felt too drained to face another flight right away. Plus there was a part of me that really wanted to end the trip the same way I started it—solo on my trusty Amtrak train which helped me gain the courage to make the trip in the first place. I envisioned reflecting on the trip and writing and mentally preparing myself to be back in my regular life. I convinced my mom to take the next flight without me—she had to be at work the next day—while I took the train home alone.

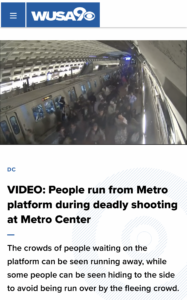

It is hard for me to write about what happened next. I didn’t share it online when it happened because it was so disturbing to me, but even more than that, it was because I didn’t want to associate the event with my trip in any way. I didn’t want it to taint my memories. It’s something I’ll write in more detail about in a later post, but I was waiting for a train on the metro platform when there was a shooting in the station. There were multiple gunshots from further down on my platform, and the rush-hour crowds and I assumed it was a mass shooting and ran for our lives. The news later called it a stampede in the station as we tried to get out. (It turns out that it was not a mass-shooting—it was an altercation between two individuals, one of whom died. But I didn’t know this until hours later.) I ran as fast as I could while carrying 60 pounds of luggage and had to jump the gate at the turnstiles to get out. It was terrifying and traumatizing, and it infuriated me.

Once I got past the terror of it, the anger arrived. Washington, D.C. is a city I once lived in and love dearly. I didn’t want it to be a place where I felt afraid. This could happen anywhere in America, I told myself, and the truth of that fact made me feel even angrier. There was a second (unrelated) shooting in a different metro station just outside of D.C. the next morning. And I was heading home to a city that’s considered one of the most dangerous in the country. It was the worst kind of culture shock. Of course this is the welcome home I receive, I thought. Welcome to America—land of casual shootings that are so common they aren’t even national news. I felt angry about gun control and the imbalance of power, and I felt the irony of people asking me if I’d been nervous or worried about safety for 5 months as a (mostly) solo female traveler. I wanted to make everyone understand—this country is where I feel afraid. Home is where I don’t feel safe. The United States is, statistically, the most dangerous place I’ve been.

I spent that night in a hotel in Washington, D.C., too shaken to even leave the hotel to get dinner. But by the next morning, I felt better. The Amtrak train didn’t leave until that evening, so I forced myself to stay awake through the jet lag by visiting the Natural History Museum and butterfly garden. I looked at models of early humans and felt my eyes glazing over. I was relieved to get on the train that evening. Then I thought about how Amtrak has basically no security checks whatsoever, and I worried about what was hidden in everyone’s suitcases. What were the chances that someone had brought a weapon on the train? Why wouldn’t they? Statistically, many people on that train must have owned a gun. They knew their bags probably wouldn’t be checked. These were the types of thoughts that kept flooding my mind. The shooting had set off the anxiety in me that my trip had done so much to cure.

A year later, it feels like the events of that journey home are a separate thing from my time in Europe. I’m glad that I don’t associate my journey with that event. But at the same time, it feels important to acknowledge the perceptions that we in the United States have about travel and safety. I feel that in the United States, we grow up in a culture that teaches exclusivity. It’s not explicitly stated this way, but the message is clear—cultures and people who are different than “us” are dangerous. Ideas different than “ours” are dangerous. Traveling (unless it’s to western countries with cultures we’re familiar with and therefore comfortable enough with) are dangerous. I felt this even more strongly on my recent trip to Mexico—this damaging narrative that we don’t even realize we’re being taught.

The truth is that the United States is, by almost every measurable statistic, significantly more dangerous than every country I visited on my trip. The truth is also that there are risks inherent to living anywhere. The narrative that we’re safe here at home and that venturing into the world is dangerous is absurd. Traveling is a way to unify people, not an unveiling of the ways we’re divided.

We rode all night and all the next day, and when we were just an hour from finally reaching New Orleans, our train hit a car. Everyone was thankfully fine, but we had to wait on the police to come and were delayed by over an hour. I must have been tempting fate, I thought, and I was relieved when we finally arrived in New Orleans just before midnight.

After 5 months of travel, I finally made it back to New Orleans. In just over 5 months, I visited 24 countries and 76 cities. I stayed in 45 hostels, 21 Airbnbs, 9 hotels, 1 friend’s house, and spent 5 nights on trains. I walked nearly 1,100 miles. I wrote more cumulative words than I had in years, and I met more people than I can count (many of whom I’m still in touch with a year later). It was exhilarating and hard and life-changing and filled me constantly with wonder. It was everything I dreamed it would be.

A friend I met in Turkey told me recently that he’d read online that it takes the time you spend traveling plus half to feel like life has gone back to normal. He asked if that were true for me. I thought for a while about whether that felt true. I told him that in the past year, I’ve crafted a new routine that feels “normal,” for sure. But what’s changed is the sense of possibility that I never fully had before this. Before this trip, travel felt possible on a hypothetical level. I could theoretically hop on a plane, but the reality of going through with it was farther outside the realm of casual possibility. It’s something that required years of planning and something as life altering as the pandemic to fully set into motion. Now that I’ve done this trip, travel feels so much more within reach. My priorities have become clearer.

This trip gave me clarity that I was supposed to be writing and exploring and that I’d have to continue to find ways to make it possible. It gave me courage to do things that at first glance, don’t seem possible, and to not worry about other peoples’ opinions. It reassured me that there is no age-limit on doing the things we dream about. It confirmed for me that money is an obstacle, but not an insurmountable one. And it taught me that I don’t need to cure my anxiety to do the things I want to do. I can be afraid and do the thing anyway.