When I got off the bus in Merida, it sounded like the birds were having a war with one another. They were tropical birds that I’d never heard before. It was November, but it felt like the middle of summer. It was far hotter than Cancun had been, and the sun was blinding. I’d left Cancun on an early bus that morning, and though it was only a 4-hour ride to Merida, it felt like a completely different country.

I barely knew anything about Merida until two or three years ago when I was restless during the pandemic and first started considering a trip to the Yucatan Peninsula. I knew a resort town on the beach wouldn’t be my ideal, and I’d never given much consideration before to the destinations on the peninsula that weren’t cruise ship stops. But when I started researching other destinations in the region, I discovered that Merida is actually the largest city in the Yucatan Peninsula and the capital city of the Yucatan state. It only gets a fraction of the visitors that the beach towns in the neighboring state of Quintana Roo get (like Cancun, Cozumel, Playa del Carmen, and Tulum.) The Yucatan state has its own culture, traditions, and food that are quite different than the rest of Mexico. Merida is considered to be the 2nd safest city in North America (after Quebec City). It’s in the same time zone as New Orleans (where I live), so working remotely would be possible, and it’s very affordable compared to the United States. Everything I learned about Merida made it sound too good to be true, and I couldn’t understand why I hadn’t heard much about it before. I used flight credits that were about to expire and booked my tickets to go see for myself.

At first, what stood out to me the most in Merida were its colors. The colors in Merida’s historic downtown rivaled those of some of the most colorful places I’ve ever seen (Burano and Cinque Terre in Italy, the Balat neighborhood in Istanbul, the island of Syros in Greece). The colonial buildings were painted vibrant neons, warm pastels, and colors so weather-worn and chipped that they looked marbled. The most worn and rustic buildings were as beautiful to me as the freshly painted ones. I like that the owners don’t feel the need to polish the history away or cover it up.

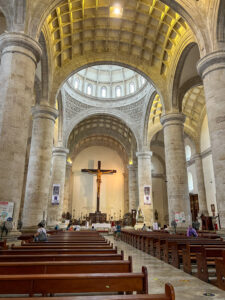

In the Grand Plaza, huge colonial mansions line the main square of the old town. Merida was originally a Mayan city named T’ho, but Spanish colonists captured it in the 1500s. Today, more than half of the population in Merida is Mayan, and nearly half of the residents speak the Mayan language. The architecture is that of the Spanish colonists. On one side of the Grand Plaza sits the Cathedral of Merida—the oldest cathedral in mainland North America. Hanal Pixan, the Mayan version of the Day of the Dead, had just ended a week before I arrived, but there were still decorations throughout town. Next to the Cathedral was a flower exhibit full of Hanal Pixan altars and mesmerizing flower sculptures.

I was staying in Merida for two weeks—twice as long as I stayed anywhere during my five months traveling Europe. Slow travel was something I’d wanted to try for a very long time, and though two weeks hardly counts as “slow travel” by most travelers’ standards, it was longer than I’d ever stayed in one place on a vacation. Though I was in the city for a couple of weeks, I was hopping around between shared rooms and private ones in a few different hostels in the city. Because my travel dates changed a few times, the most affordable and highest rated Airbnbs were no longer available for the full two weeks, so I decided to sample all of the best hostels in the city instead.

I spent the first few nights in a shared room in Che Nomadas Merida Hostel—part of a popular local hostel chain with a younger and louder crowd than I typically like. But they had a co-working room with very good wi-fi and a giant pool. I designed an odd hodgepodge of a work schedule for myself while I was in Mexico. I’d worked remotely once before while traveling on the Amtrak trip that Michael and I made to Canada (which I wrote about here, here, and here). It didn’t go well. On that trip, I’d tried to work remotely during long hours on the train. In theory, this would have been fine, but the reality was that Wi-Fi was never reliable on the train, and trying to work was always a nerve-wracking hassle. In Mexico, I made sure that I was only working on non-travel days when I had a co-working space in my hostel or a private room. I arrived in Merida on a Thursday, worked half that day and then Friday and Monday, and then I had the rest of that week off before starting a new role in the same company the next week. I started my new job the week of Thanksgiving, so I only worked that Monday and Tuesday. The next week I worked another couple of days and then took one day off to fly home. My work schedule is not interesting, I know. My point is that you can have a full-time job and still figure out creative ways to make travel work.

I follow a lot of travel influencers on Instagram, and I cannot count the number of times per week that I see someone trying to convince me (and by me, I mean the general public) to quit my job and travel full time and magically start making six figures by watching some videos on SEO and making listicles while floating in a hotel pool. They drive me nuts. And while there are certainly some people who DO make six figures doing this (with what I assume is a lot less glamour and more hard work than their Instagram grids would have you believe), that’s not a reality that is feasible for most people. What IS feasible for far more people is traveling more and for longer by getting creative with budgets and holiday time. And in my case, having several very persistent-yet-polite conversations with HR when they try to tell you that you can’t work remotely while abroad even though you have a job that is… remote. Polite persistence is underrated. So when you picture me “working remotely” while traveling, please do not picture me with a cocktail in a hammock. Picture me instead in pajamas in a hostel bed because the room doesn’t even have a desk. (I’m not complaining. I’m very lucky to have a remote job right now.)

During my first few days in Merida, I did a lot of wandering. I zigzagged up and down the streets, past restaurants and boutiques and the antique store with the hairless dog who quietly greeted guests while wearing her red dress. (I saw her every day and learned that her name is Yo-yo. She’s perfect.) Because I was working those first couple of days, I did most of my wandering after dark. Though I’d heard how safe the city is considered to be, I didn’t know if I’d feel entirely comfortable walking around at night. I absolutely did, though. Downtown Merida comes alive at night, so unless you’re out until the early hours of the morning, you’re sure to be in well-lit streets full of other people and busy restaurants.

Not for a moment in Merida did I feel unsafe. Sometimes I’d see officers riding through town standing in the back of what looked like military trucks with big guns. I remembered seeing the men carrying machine guns in the back of trucks 20 years ago in Nuevo Laredo. This was nothing like that. These were men in uniform, clearly official security. Passersby hardly glanced their way. Instead of making the public feel nervous, I got the impression that they gave the public added assurance. I felt far safer in Merida than I ever do at home.

Merida isn’t a city that has a ton of must-see attractions, and I think it’s for that reason that a lot of tourists only stop in Merida for a couple of days to use it as a base for day trips. They’re missing out though, because Merida has an incredible amount of free cultural activities. Merida was named the first ever American Capital of Culture, and it’s the only city that has been given the honor twice. Every night in the Grand Plaza, there’s a different cultural activity to see. They’re perfectly timed so that you can do a day trip and still get back in time to see them. On Fridays, there’s a huge game of Pok-ta-Pok—an ancient Mayan sport that’s sort of like basketball and volleyball, but you’re not allowed to use your hands. The players dress in traditional Mayan costumes and use their hips and some kind of physical sorcery to put the ball through the high hoops. At one point they even play with the ball on fire. When people ask me if Mexico was dangerous, I think of the fire volleyball game. A couple nights of the week, huge bleachers are pulled into the street in front of the Cathedral, and there’s a light show projected onto the face of the Cathedral that shows/tells the history of Merida. One night, there’s a big public dance where all the locals come salsa dance in the street together. And one night, there’s a dance performance with traditional costumes and local music.

My favorite cultural event of the week is on Sundays when art vendors set up booths throughout the Grand Plaza and one side of the grandest boulevard in town, the Paseo de Montejo, is closed for traffic so that everyone can come rent bikes and take leisure rides past all the mansions. The bike I rented cost me 20 pesos to rent for an hour. That’s like $1.10. There was no helmet and no real paperwork—they just took my license and gave me a bike. There were tandem bikes and odd bike creations and rollerbladers and lots of dogs. Dogs being pulled in carts. Dogs sitting in bike baskets. Dogs in backpacks. Dogs running. So many dogs.

On my first weekend in Merida, I decided I needed a crash course in Mayan history. I remembered learning the basic facts of Mayan history in middle school, but the Maya, Inca, and Aztec specifics get very blurry for me. It’s not history that I continued studying in college the way I did with European history, and I’d lost a lot of it. So I took an Uber to the Mayan World Museum of Merida to learn all about it. I was so impressed with the place. I’ve never been in a museum so interactive and so good at engaging audiences with historical information. I learned all about Mayan history and Mayan culture and remembered a lot of things I’d forgotten having learned in school 20 years ago. It was a 20-minute Uber ride (one-way), but it only cost $7. A ride that long back home would have cost at least five times that much.

After my first weekend in Merida, I finished my last day of work in my old job that Monday. I’d spent four nights in Merida already, and usually when I travel, I’m used to packing up and heading for a new place after that many days. This time, I had a whole week of jobless freedom in front of me to get to know a whole new side of the city.