The first time I ever left the United States was on a mission trip to the Mexican border when I was in 9th grade. When I think about how I started traveling, I often accidentally overlook this trip. I think instead about the first time I flew on a plane when I was 17 and about getting my first passport and traveling overseas for the first time at 21. I think about how the first time (in my memory) that I’d ever been more than a day’s drive from home was when I was visiting colleges before my senior year. I think part of why I accidentally overlook that trip to Mexico as the first time I traveled internationally was because it was always a hard trip for me to categorize, and I was never quite sure if it counted. (We slept each night in Texas, so did I really “travel internationally”?) And part of it is because I never figured out how to talk about it without treading in territory that felt too delicate.

In middle school and high school, I went to a large church in my Mississippi town that had a very active youth group. The details are a little blurry now, but I believe there was a missions committee in my church who partnered with a team in Mexico and was working on helping them build a church in a neighborhood of Nuevo Laredo, just across the Texan border. For several years, there was an open invitation to any high school students (with parent permission) and adults in the church who wanted to join the annual spring break trip to help. My sister went on the trip during her senior year in high school, and the following year, when I was 15 and therefore eligible, I told my parents I wanted to go.

On the surface, this might seem wildly out of character for me. (As an adult, I’m skeptical of most short-term service trips like this.) But in retrospect, it makes perfect sense why I wanted to go. First, it was the only opportunity I’ve ever had to go on an international trip, and the fact that it was very inexpensive made it seem like a chance I couldn’t pass up. I had taken two years of Spanish class, and I was desperate to try out my (very meager) attempt at communicating in a Spanish speaking country. I knew that this would NOT be the kind of mission trip that included any proselytizing in the streets by anyone. Even at 15, I knew that was something I didn’t want to be associated with. And it also makes perfect sense that I was unbothered by the fact that none of my close friends were going. I didn’t know yet that I’d go away to college and then grad school where I didn’t know a soul, that I’d love the anonymity of moving to cities where everyone was a stranger, that I’d fall in love with solo-traveling and never fall out of it. All I knew at the time was that I wanted to go to Mexico, and no one else’s concerns or opinions persuaded me to reconsider.

This was nearly 20 years ago. It feels impossible that I was a teenager 20 years ago with many naïve thoughts but also with many thoughts that my 34-year-old self would still think today. I didn’t have a passport. 20 years ago, you didn’t need a passport if you were only crossing the border for a day trip. (Is this still true?) 20 years ago, I had only a vague awareness of the growing problem of the drug cartels on the border. 20 years ago, I felt that if the men of the church who knew my parents and who I respected, thought that this trip was fine and safe, then it certainly was. My parents didn’t have cable yet. We’d only just gotten the internet. Accessibility to the media was so different. I had no real cultural understanding of where exactly we were going.

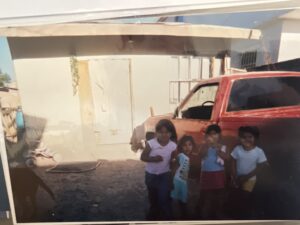

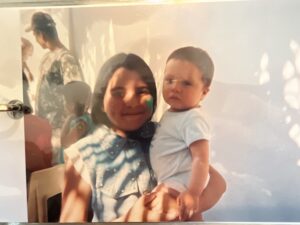

During the week we spent there, we slept in a big house for service groups like ours in Laredo, Texas. Our showers were not allowed to last longer than 5 minutes, the walls were made of bare cinder block, and the cooks served something called “mystery casserole.” Each day we’d cross the Rio Grande into Mexico. One day we volunteered at a nursing home. One day we did construction work at an orphanage. One day we visited a youth detention center where some of our group played soccer with the boys imprisoned there. We didn’t go in with agendas to spread a religious message. None of us would have had the language with which to do that if we’d wanted to. We just went in to share smiles and kindness, to knock down walls with sledgehammers and to serve food or hold a hand. But we spent most of our time at the new church that the men were helping build. It was in a small neighborhood where chickens roamed the streets freely and families of 7 or 8 lived together in one-room shacks. Mostly the other young people and I played with the kids who wandered up while the men did construction. We brought dolls and little toys for them. My favorite of the kids we met was Nayeli who lived down the street. She knew a few words of English and I knew a few words of Spanish. She was probably 9 or 10 at the time, which I thought of as a little kid, but now I realize that means she was barely younger than I was, that she is nearly 30 today. She colored a picture for me as a goodbye gift, and I have it still. I remember how happy everyone seemed. I remember thinking that despite having nothing by the standards I was used to, they were so happy.

And I want to make very clear—I am not making any statement about morality or ethics here. I am not making any religious statement here. I will say that I would not choose to go on such a trip today. I will say that I had never heard of or given thought to concepts such as a “white savior complex” at the time. (Had any of us?) The trip probably had a greater impact on those of us who went than on those we were aiming to help, but I also don’t regret having the experience.

During our free time, we visited a local restaurant where a mariachi band sang to us and the local market where we could make silly attempts at bargaining. While walking the streets of downtown, we saw trucks pass carrying men who were holding machine guns in the truck beds. They would fly by, the guns bigger than my body. My 15-year-old-self did not know anxiety. Did I assume these men were official security? That they were the “good guys?” (Were they?) I don’t recall them wearing uniforms or looking remotely official. When we were pulled over one day and an officer with a gun got on the bus, scanning each of our faces before getting back off, did I feel nervous? I remember collectively we felt nervous, that we giggled about it afterward, but was I at any point truly afraid? I don’t believe I was.

I think that trip gave me a lot of things. It wasn’t a city with a tourism industry, it wasn’t pretty, and the food was not particularly good, but still I loved it. I think it opened my eyes to the type of inequality I had only previously heard about but never seen. I think it allowed me to practice a level of open-mindedness that I’d never had a chance to practice before. I think it made me feel bold to know that I could go on trips to faraway places without close friends to use as a social crutch. It was my first real glimpse of a culture different than my own. And I think it was several years before that narrative really changed for me.

We intended to go to a different city in Mexico for the following year—the city of Monterrey, where we’d need passports and get to sleep on a rooftop under the stars. I had already signed up, eager to go back, and I took another semester of Spanish to prepare. And shortly before we were set to go, the trip was canceled. The drug situation on the border had ramped up and gotten too dangerous, the church committee said. It wouldn’t be safe for us to go.

Years after the fact, I looked back on my memories of those men with machine guns and thought, what on Earth were we doing there? Was there ever a reality in which that was safe? I think about the person we saw swimming in the Rio Grande as we crossed it on foot. I think about the trucks we saw chasing a car through the streets. Was it arrogance or naivety that led us to assume that no harm would come to us? Was the drug-related crime on the border in its infancy at the time and no one knew it, or was this a case of the church assuming faith provides protection? I truly don’t know. But I do feel strongly that Neuvo Laredo, Mexico in 2005 was the most dangerous city I’ve ever visited. And in the years that followed, it felt more and more upsetting because it felt like the media kept propagating the situation into a broader and deeply troubling stereotype.

The Mexico of the media became a terrifying place where you’d surely be kidnapped or killed. At first the media focused only on the border towns, but in more recent years, the media began to imply that nowhere in Mexico was “safe.” This isolated event happened in Cancun, therefore it’s not safe. This gang activity happened in Baja, therefore it’s not safe. Why is this not the standard we hold any American cities to, I wondered. I remember the fury I felt hearing Donald Trump’s comments about Mexico in 2016. I felt defensive and infuriated every time I heard gross stereotyping—but wasn’t I a hypocrite? Wouldn’t I be lying if I didn’t admit that I wouldn’t allow a group of young people to go on the same trip I’d made and that I didn’t think we should have gone, either? Am I being prejudiced or stereotyping to say that I’d caution anyone to avoid Mexican border towns today? That’s different, I’d rationalize to myself. One town or region doesn’t represent an entire country. A group of people doesn’t represent an entire population. I recently wrote a blog post about the United States being the most dangerous country of my 5-month trip last year, and I don’t feel conflicted saying that. So why do I feel responsibility to defend the cultures that aren’t my own? Is it because I feel guilty being part of the culture misrepresenting them?

I didn’t need proof that the media was sensationalizing and misrepresenting Mexico to know that it was true. I knew that with 100% certainty, even if I never visited Mexico again. But… I wanted it. I wanted an updated memory. I wanted to see Mexico from the perspective of a person who has now traveled to many other cultures that US media has misrepresented. Like my 15-year-old-self, I still wanted to practice Spanish. I want to be bold still in the way my 15-year-old-self was. And so, a few months ago, I decided it was time to go back to Mexico.