In 2017, I was struggling so much that I don’t recall paying a lot of attention to the North American eclipse until it happened. At the time, I was unemployed, living at my parents’ house, and juggling a half dozen tutoring gigs while I applied to as many jobs as I could find. My parents had to work on the day of the eclipse, and I decided that morning that an eclipse was a significant enough event that I should do something special for it. I made myself a cereal box eclipse viewer with craft instructions I found online, then I drove an hour to the INFINITY Science Center (the NASA Stennis Visitor Center) on the Mississippi Coast. I think I was the only person over the age of 8 who was there without a child, but it was still an unexpectedly delightful time. There were arts and crafts, special exhibits in the museum, and lots of enthusiastic scientists. We only saw between 80 and 90% totality that day, but it still felt monumental as the sliver of sun got smaller and smaller in the sky.

Afterward, my mom (the biggest enthusiast I know of all things related to weather and astronomy) and I regretted that we hadn’t made the day-long drive up to Nashville to see totality. We decided then that we’d try to see the next one. Michael also decided in 2017 (before we met) that he’d travel to see the next one. He and I started discussing an eclipse trip to Austin a year ago, and my mom agreed to join us. (I’d like to note that my dad was invited as well! But after spending 20 years as a cross-country trucker, he enjoys being at home more than he enjoys a road trip.)

In June, I booked our Austin Airbnb, and we ordered our eclipse glasses an embarrassing number of months in advance. Our enthusiasm knew no bounds. It was a couple months ago that the obstacles started popping up. Just a few weeks ago, our Airbnb host canceled on us without a real reason. (Something about a smell of mildew that he didn’t plan to address in the 6 weeks between then and the eclipse.) The Airbnbs that weren’t already reserved in the area were 5 times the price that we initially paid. We worried we’d have to cancel entirely, but I finally found an Airbnb that was way more expensive than what we originally paid for a night less than our planned stay. But it was half the price of any other option. I gritted my teeth and booked it.

A couple weeks out, the weather reporters were already predicting a disaster. As our departure day got closer, the chance of storms became more and more likely. The week before the eclipse, a lot of people started canceling their eclipse trips to Texas. We considered doing the same. My mom and I didn’t need to miss the days of work, and it was a lot of money to waste if we ended up not being able to see anything. But it was too late to cancel our Airbnb, and I worried we’d regret it if we didn’t try.

So over the weekend, we made the 9-hour drive to Austin. I’d been to Austin a couple times previously, but my mom had never been. I took her to see the Congress Avenue Bridge bats at sunset and brought her to eat at the food trucks near Barton Springs. The weather forecast for the eclipse had slightly improved—clouds were predicted for the entire day, but the tornadoes and hail were at least supposed to hold off until a couple hours after totality.

Because Austin was on the very edge of the path of totality, the total eclipse was only going to last about a minute and 40 seconds in the city. Since we figured the clouds would prevent us from seeing anything other than a noticeable difference in darkness, we thought it was worth driving closer to the center of totality where we could at least see a longer period of cloudy darkness.

We woke up that morning, studied Google maps for a while, and looked up the hourly forecast for every small town within an hour and a half west/northwest of Austin. We settled on Llano, Texas, a town of 3,500 people that I’d never heard of, because the Weather Channel website predicted one more hour of “partly cloudy” weather instead of just “cloudy” weather there. Plus, it was nearly on the middle line of the totality path. We drove the hour and a half through the hills to get there under a sky full of gray clouds.

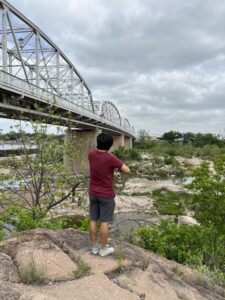

Llano looked like a movie setting for small-town Texas. (Google tells me that it has the largest population of white-tailed deer in the United States. Who knew?) There’s a river running through the small downtown, and crowds were gathered on both sides when we arrived. One side was reserved for those who had paid in advance to camp on the riverbank and have prime viewing space. The other side was open to the public. I could tell the town must have planned for more visitors because we were able to park right away and for free. The line of porta-potties was bigger than the crowd necessitated, which meant they were all mercifully clean. The crowd on the riverbank was large enough to feel communal but not so large that it felt cramped. We even found an unoccupied bench to sit on.

I’ve never seen more enthusiastic nerds in one space. (To be clear, I’m including us in the category of “enthusiastic nerds.”) There were so many telescopes with attached cameras that probably cost more than my car. There were so many eclipse t-shirts. (Yes, I obviously bought one, too.) There was so much nervous anticipation. I brought my cereal box eclipse viewer and our colander, and we fit right in.

Then, for reasons that are hard to articulate, I started to get very nervous. I don’t quite know how to describe this feeling, and I haven’t heard many others express it before, but it’s a thing that happens to me every time I am faced with something greater than my understanding. I can probably attribute this to my childhood in a hyper-religious community where everything was interpreted as prophetic. Rare celestial events make me nervous. Big natural disasters make me nervous (even if they happen on the other side of the world). I thought about how the ancient Myan’s studied the skies to understand the world. Their observations created one of the most accurate calendar system’s the ancient world ever saw. To the Myan people, solar eclipses were a battle between the gods that required human sacrifices. In ancient China, solar eclipses were said to occur when a dragon attacked and ate the sun. The ancient Greeks thought eclipses signified that the gods were angry with humans. Though I, of course, understand the science of what’s occurring during an eclipse, there is part of me that can’t escape feeling uneasy and mystified by them.

For the hour leading up to totality, the sun peeked from behind the clouds every few minutes, so we could see the crescent shrink through our glasses for a few seconds at a time. And then something inexplicable happened. As totality got closer and closer, the clouds just… parted. In the spirit of Biblical metaphors, it truly felt like Moses and the Red Sea. Minutes before totality, the clouds dissipated around the sun. And as sky turned dark and the crescent of the sun turned into a bright diamond, we had an unobstructed view for the entire 4 minutes and 24 seconds.

I don’t think a person can predict the emotions they might feel during a total eclipse if they’ve never witnessed one before. The crowd was full of nervous giggles, cheers, gasps, and undiluted awe as the sky grew suddenly dark and the streetlamps came on. The diamond glowed bright in the sky, and planets appeared near it. I never realized how the most miniscule sliver of sun lights up the world, and how suddenly darkness occurs once the sliver is gone. The temperature dropped what must have been ten degrees, and the crowd got quieter as everyone watched, transfixed. My nerves disappeared, and I felt close to tears. It felt more humbling, unifying, and mesmerizing than I have words to adequately explain.

And then suddenly the sunlight was back, and the crowd cheered like their favorite band had returned to the stage for an encore. A few minutes after totality ended, the clouds returned. I later heard people across Texas say the same thing—the clouds parted for their view—the most humbling and awe-inspiring gift in response to our low expectations. Don’t underestimate me, the sun laughed.

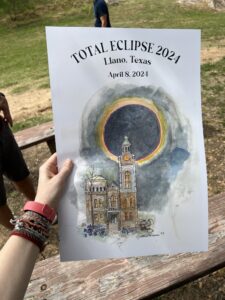

I bought a water-color print of the eclipse that a local artist prepared for the event so that I have a piece of this memory and of Llano to hold onto. We went to a few shops in downtown after totality in search of eclipse souvenirs. The shop owners couldn’t have been more welcoming or excited to host visitors. I can’t imagine a more perfect place to have experienced this memory.

And now I’m looking at Northern Spain in 2026 and thinking that that sounds like a great time to finally hike the Camino de Santiago.