On the way back to Split, Croatia, we wove around terrifying and beautiful cliffside roads along the Adriatic. I was determined to make the most of my remaining time in Croatia. Getting Covid on my second day in the country had derailed several of my plans, and I was glad that I still had enough time to reorganize some of the plans I’d had to change. I’d gotten a brief glimpse of Split, the second largest city in Croatia, already when I spent a night there on the way south to Dubrovnik, and I was excited to go back and spend a few days fully exploring it.

Walking from the bus station in Split to Old Town with my luggage was so much easier this time than it had been 5 days earlier when I was so weak from Covid. My Airbnb host allowed me to check in early when I arrived that morning. She met me to give me the key and show me my apartment. It was tucked in a hidden corner of Old Town just outside the palace walls, and I would have had no hope of ever finding it with an address or directions. There was construction in the building, and the floors in the apartment had soft spots that creaked so loudly when I stepped on them that I was certain the floor would fall through, but it looked newly renovated and had a full kitchen and plenty of space—a $60 splurge that I thought I deserved after enduring a week of Covid in a tiny hostel room with a shared bathroom. I found a small laundromat hidden within the labyrinth of Old Town where I washed all my clothes then brought them back to my apartment and hung them on every available surface to dry.

That evening, I did a walking tour to learn more about the history of Split. The city was first founded as a Greek colony and later became the royal palace for the Roman Emperor Diocletian in 305 CE. It’s an ancient city that feels modern. It was strange to be only two hours from Mostar but to see no physical evidence of the conflicts of the recent decades. Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia before Bosnia and Herzegovina did, and the Croatian War of Independence lasted 4 years. But Croatia avoided the brunt of the fighting—they lost 20,000 citizens to Bosnia’s 100,000. The war feels like a more distant memory in this region of Croatia.

The financial situation in Croatia felt like a stark contrast to that of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well. Tourism has exploded in Southern Croatia in the past couple of decades. It was once a budget travel destination, but on the coast during tourist season, prices have risen dramatically. It’s been a blessing and a curse for the local people. On one hand, the tourism industry has created a lot of jobs and brought a huge amount of money into the local economy. On the other hand, the rising prices have driven many locals out of their cities. Salaries in the region can’t match the money tourists bring in, and inflation has become a big problem.

A major event that I’d been hearing about since I’d arrived in the country was Croatia finally becoming a Schengen member. The Schengen Area is a collection of 27 (mostly) European Union countries that essentially function as one state in regard to border control. So basically, once someone is checked at a Schengen border country, they can travel freely within the Schengen Zone without being rechecked. With a United States passport, a person is allowed to spend up to 90 days in the Schengen Zone within a 180-day period. When I’d planned my trip, I’d had to carefully plan around the Schengen day limit, making sure I was dipping out of the Schengen Zone for enough days that I wouldn’t surpass 90 within it. Until the end of 2022, the only former Yugoslav country in the Schengen Zone was Slovenia, and Greece was the only member country on the Balkan peninsula. If I’d done my trip just a couple of months later, I wouldn’t have been able to do the same itinerary because it would have meant overstaying the Schengen limit. There are several other Balkan countries trying to join the Schengen Area, and it’s likely that several of them will be accepted in the coming years. Changes like this were what made me feel such urgency that, in spite of what many people would say was good financial sense, the time for me to take this trip was now. I would quite literally never be able to do this trip again.

Becoming a Schengen member also meant adopting the Euro. For 28 years, the currency of Croatia was the Kuna. One Kuna was about 15 US cents while I was visiting. But starting in January of 2023 (just 2 months after my visit), the Euro would become the new official currency. People felt apprehensive about what this would mean for locals. My taxi driver in Dubrovnik told me how few locals can live in Dubrovnik now because they can no longer afford it, and people are worried that the change in currency will raise prices even higher. My tour guide in Split said that he wasn’t sure how the change in currency would impact the economy. He explained that one remarkable thing about the region is that even though salaries are low, and unemployment is rampant, hardly anyone is homeless. As in neighboring Bosnia, there is a tradition of grandparents leaving their property to grandchildren, so even families living in poverty own homes. And after I thought about it, I realized that I don’t believe I saw one homeless person anywhere in the Balkans.

My friend Tom, who I met in Zagreb, had spent a week up the coast in Zadar while I was sick and in Bosnia, but he’d traveled to Split just before I did. We got dinner and talked about where we’d go next. For me, this was determined by months of research and meticulous planning. For Tom, this was determined by googling which cities had the cheapest flights a day in advance. He spent some time trying to convince me to hop on a $16 flight to Bulgaria that left in a couple of days “because why not?” He had maxed out his 90 allowed days in the Schengen Zone, so he was planning to head to Asia once the beach towns in Southeastern Europe got too cold. I was excited for winter. It was an unlikely friendship, indeed.

The next morning we decided to make a day trip to Hvar. Hvar is one of the most famous islands in Croatia and a known party town during the summer season. I typically stay away from party destinations, but in late October, our ferry options were limited, and Hvar was the easiest day trip. We left early that morning and sat on the upper deck of the ferry where we could see dolphins jumping as we headed to the islands. But when we arrived at Hvar, the town was almost entirely closed. It was something I’d assumed I would encounter on my trip once the tourist season ended, but Hvar was the only place where it actually happened—a whole destination nearly emptied out. The harbor was beautiful, but it was almost eerie to see it so devoid of people. Most restaurants were closed, and the one tourism office that we found open told us that most businesses wouldn’t be opening until spring. The only things she could suggest for us to spend the day doing were to swim or climb the fortress. Tom wanted to take a boat tour to see the Blue Grotto cave, and the woman told us there were none. We grabbed an overpriced breakfast at one of a couple of cafes we found open in the main square, and then I decided to catch the next ferry back to Split even though we’d only been on the island for a couple of hours. If I didn’t catch the next ferry, I’d have had to wait 6 hours for another one, and I decided I wanted to prioritize the many things I still wanted to see on the mainland. (Tom stayed and DID end up finding a tour to take him to the Blue Grotto, so it all worked out in the end.) I’d love to go back to Hvar and see the entire island, but next time I will either devote more than one day to explore more of the island by bike or scooter OR I will go before the tourist season entirely ends.

Back in Split, I ate gelato for lunch, visited a tiny Game of Thrones museum that I was very unimpressed by, zigzagged the maze of Old Town until I’d memorized it, and got a way-too-expensive dinner. I watched the sunset over the harbor, and it occurred to me that the sun hadn’t seemed to set quite so early the previous days. It wasn’t until the next day that I realized the time had changed without me noticing. I never knew that Daylight Savings Time ends a week earlier in Europe than it does in the United States.

On Halloween morning, I took the bus to a beach on the outskirts of Split for an Airbnb Experience I’d found online. A local no-kill animal shelter, Bestie Split, hosted this weekly event where you could sign up and pay a fee (which went toward shelter costs) to hang out with a shelter dog for a couple of hours. They drove a van with enough dogs for everyone to the “dog beach,” and each guest was given a dog to walk. A couple of days before this, my long-term-foster dog back home, Chewie, had had a terrible health scare. She’d somehow gotten into a bag of dark chocolate chips and eaten an amount that would have been fatal if Michael hadn’t miraculously gotten home in time to find her and rush her to an emergency vet. She got to go home the next day and was feeling back to normal, but it was the kind of emergency that I worried about before beginning my trip, and it made me miss Chewie even more than usual. The next best thing to seeing Chewie was to hang out with another dog who needed help. My dog for the morning was Roko—a skeletal little hound who was severely malnourished and likely blind in one eye, but he was so excited to play. Roko and several other dogs had come from a shelter a few hours away in Dubrovnik that was being shut down because of neglect. He had bad health problems, and they hadn’t felt he was ready to do any of their volunteer events before, but he was so eager to get outside that they decided to bring him that day. I adored him. Our host told us all about the shelter and the work they do and how our money would help them. It’s a brilliant marketing plan that more shelters in tourist hubs should do—anyone who is missing a dog while traveling would love to pay a fee to help shelter pets get exercise. We walked along the beach, and several of the dogs swam like they had never been happier. I wished I could bring precious Roko home with me to be Chewie’s brother, but I gave him back and bought one of the shelter’s t-shirts instead.

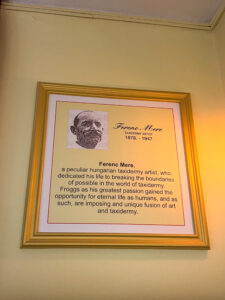

Afterward, Tom and I went to the frog museum—Froggyland. Halloween isn’t really celebrated in Croatia, but I adore Halloween, and it seemed important to do something to commemorate the day. When Tom told me that he’d heard there was a frog museum, I knew that was exactly the right thing. We found it on Google maps and headed straight there and found one of the more absurd establishments that I’ve ever visited. The museum was small—just one long room—but it was entirely full of taxidermied frogs—over 1,000 of them. All the frogs were arranged in different “life scenes” with horribly translated descriptions. There was a circus scene, a playground scene, a party scene, a blacksmith shop, a school… At first I couldn’t figure out if the frogs were real. I mean, if they were once-living frogs or plastic ones. But the hint of formaldehyde in the air made me suspect the truth. Then I found the plaque on the wall that revealed the name of the man who made it his life’s mission to taxidermy all these frogs. If you find yourself in Croatia on Halloween, I can’t think of a better way to celebrate.

Tom had a work call that evening, and then we were going to get dinner, and this is the part of the story where, yet again, things go wrong. It started with my stomach not feeling well. And then the chills arrived. And then the aches and fever. And then it was clear that I had a stomach bug. By 4:00am, I was in bed, heater on and covered in every blanket I could find, shaking.

It felt so disheartening to be in the situation again where I was stuck and forced to change my plans. It had only been two weeks since I’d gotten Covid in Zagreb, but at least then I’d already had 3 more nights booked. This time, I was supposed to be checking out of my room early the next morning. I was planning to spend the day in Sibenik and then spend the next two nights in Zadar with a day trip to Plitvice Lakes (a day trip I’d rebooked after having to cancel it when I had Covid). It was clear that there was no chance I’d be able to get on a bus or even leave the room anytime soon. I started messaging my host as soon as the sun rose, hoping desperately that my room would be available to extend my stay. I was too sick to move. Thankfully they responded quickly, and they were so very kind. They let me extend my stay for a far cheaper price than I’d paid for the first three nights there. (I ended up having to add a 5th night that they let me add for less money, too.)

Being sick this time was harder than it was in Zagreb. For one thing, I was alone. Tom knew I was sick, and if there were an emergency, I knew I could ask him to help, but it was different than being sick in the hostel where I had the comfort of knowing that my host was in the same building if I needed something. I was also much sicker than I’d been with Covid. I tried to walk to the nearest grocery store a few blocks away for crackers and Powerade, and I got dizzy and nauseous just trying to get there. I think that having lived hermetically sealed and not exposed to anyone for 2 and ½ years and then getting Covid had weakened my immune system so much that I likely got much sicker than I would have otherwise. But again, as was the case when I got sick two weeks prior, it was probably the best time that it could have happened on my entire trip. Missing out on what I’d wanted to do in Croatia was horribly sad, but it could have been so much worse. Getting sick in Western Europe would have meant running out of money I needed for the remainder of my trip, and it would have been awful for an illness to derail Michael’s portion of the trip or the non-refundable Turkey tour that we’d booked 2 years in advance.

It was the beginning of November, and I spent those first two days stuck inside watching Netflix and shivering. But I also decided that I’d do something I’d wanted to do since I was 15—I’d do NaNoWriMo—a popular writing challenge where you have the goal to write a 50,000-word draft of a novel during November (National Novel Writing Month). I had a head start with the manuscript I started in Romania, and I decided that maybe being stuck inside those days was a gift to nudge me toward committing to finish it. I would not advise getting Covid and a stomach bug back-to-back while on vacation in Croatia, but if you find yourself in such a predicament, I recommend making sure you pack your thermometer, covid tests, Tylenol, Imodium, Pepto, and very warm socks. I guarantee that you will not regret it. (And when your travel partner gets food poisoning in Macedonia, he will be grateful for your overpreparation, as well.)