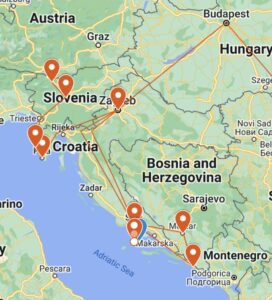

Once I was well enough to travel, I had to make a choice. I could either extend my time in Croatia and try to squeeze in the things my illnesses had caused me to cancel, or I could pick up with my itinerary as I’d originally planned it. It wasn’t an easy decision, but it felt like an obvious one—I needed to keep going. Staying longer in Croatia would have meant cutting my time short in Slovenia or Italy, changing room reservations that would have meant losing money, and missing out on events I’d planned for the coming weeks. I’d run out of wiggle room, and I couldn’t fit it all. So I didn’t get to see Plitvice Lakes or Krka Waterfalls, and I didn’t get to visit Sibenik or Zadar, and I never got to do the ghost tour in Split. And for a little while, I was very sad about those things. And then I snapped out of it and remembered how lucky I was that THAT was the big tragedy of the trip. Really it was just incentive to go back and see Croatia again, just like I want to go back to see Ireland, Kosovo, Ukraine (when it’s possible), Georgia, and more cities in Albania. Those were all places on my original itinerary that I ended up having to change. There’s nothing wrong with feeling sad when plans you looked forward to change, and it doesn’t mean that you’re any less grateful for the journey exactly as it was.

Because I was skipping cities I’d planned to spend nights in, I had to reroute my way to the Istrian Peninsula—the Northwest region of Croatia where I was spending the next 3 nights. It meant one of the longest travel days of my entire trip. I woke up at 6:00am, decided I felt good enough to attempt the journey, and made the impossibly slow walk to Split’s train station. The train took considerably longer than the bus, which I’d used for this route previously, but I had not yet recovered enough from my stomach bug that I felt safe to be without access to a bathroom. And I’m very glad I picked the train because the views were stunning. No one had told me that the train ride from Split to Zagreb was a train enthusiast’s dream, so I’m here to tell you now. For 6.5 hours, we wove our way up the coast through the mountains around shockingly quick curves and cliffsides so high they made my heart pound, but the views were too beautiful to stop looking. It felt more like a rollercoaster than any other train I’ve ridden. There was no direct route to get to Istria, so I had to take the train all the way to Zagreb and catch a bus from there. I fell asleep before we got to Zagreb, and I jerked awake disoriented to see everyone standing to get off the train. My stomach was feeling better, so I decided to continue on and brave the bus ride to Pula.

After 12 hours of traveling, we finally made it to Pula, and I ordered delivery from the only restaurant still open and ate my first real meal in 3 days. My Airbnb was adorable, the bed was comfortable, and I felt relieved and a little shocked that I’d made it.

The next morning, I woke up with a headache, but my stomach felt better, and I trusted that I had finally turned the corner to being well again. Pula is an adorable town that’s largely empty of visitors in November, but I didn’t mind. I was moving slow, and it was nice to be in a place where I didn’t feel urgency to cram too much in.

Though Pula is quite small, it’s the largest town in Istria. Because of its position on the water, it used to be a major port in the Adriatic. It felt more like Italy than Croatia. This region was once part of the Roman Empire, and there are still 2,000-year-old arches, temples, and a large amphitheater (one of the most complete and best-preserved Roman amphitheaters). You can still walk through the underground passages that the gladiators used and see the cisterns that brought water to the spectators in the amphitheater. One-thousand years after it was built, Medieval knights still used it for tournaments.

After exploring the amphitheater, a sudden rainstorm sent me seeking shelter in the nearest open business I could find—the Olive Oil Museum. The region of Istria is known for its olive oil production, but it’s not mass produced here the way it is in Italy and Greece. Because it’s mostly produced in small batches at family-run companies, it’s less likely to find its way into our grocery stores and more likely to be consistently high quality. The woman at the counter explained the ticket options. I could pay the regular ticket fee to see the small museum, or for an added fee, I could do an olive oil tasting. I had no idea what an olive oil tasting entailed, but it cost $18, and I was eager to have a place to sit and rest during the rain. So I paid for the tasting. I did not know at the time that I was the ONLY participant doing the tasting, so it ended up being a private lesson and an activity I’d recommend to everyone. My instructor led me to a gorgeous, industrial kitchen clearly designed to accommodate groups. She showed me a PowerPoint and explained what classifies olive oil as “extra virgin” and why the olive oil that we buy in most grocery stores can technically be classified as extra virgin even though they are nowhere close to the standard of extra virgin olive oil that has true health benefits. And then I did a tasting where I got to sample several types of olive oil and learn the difference between what’s considered high quality and low quality. I learned that I had never tasted high quality extra virgin olive oil in my life until that moment. It turns out that high quality olive oil tastes spicy and not at all like olives. Who knew? I even got a special dessert that consisted of yogurt, olive oil, and dried figs, and that sounds disgusting but was actually delicious (says the lactose intolerant person).

My headache was even worse the next morning, but I packed my bags (which I still felt too weak to carry) and headed to the station to catch my bus to my final destination of Croatia—Rovinj. I caught glimpses of the Adriatic through the vineyards and olive groves outside the bus window on the 45-minute ride there. My Airbnb in Rovinj was right in the center of the Old Town which was like something from a storybook. It was a tiny maze of cobbled stones weaving around a hill, and trying to walk on them with luggage felt as perilous as ice skating. I didn’t mind. Walking slower meant more opportunities to take photos. Like Pula, Rovinj was a former Venetian town and looked more Italian than Croatian. Again, I had the town largely to myself, and I watched one of the most beautiful sunsets I’ve ever seen from the hilltop church where a wedding had just taken place. I wandered around and around the town, startling stray cats and dipping into tiny art shops. It looked too idyllic to be a real town, but the laundry drying on clotheslines across the alleys over my head and the small dogs that locals walked past me were reminders that there are people who truly live in places this beautiful.

The next day, my headache was worse than ever, and I was starting to worry. In my regular life, I have pretty severe health anxiety—a fancy and diagnosable term for hypochondria. I hadn’t felt that kind of anxiety very much on my trip at all, and I even surprised myself when I felt fairly calm while sick with Covid in Zagreb. But my headache had lasted for days and only gotten worse, and the anxiety I started to feel about it felt nearly debilitating. The pain throbbed behind my eyes and spread throughout my head making me feel dizzy and sensitive to light. I’d never had a migraine before, so I didn’t know what to call this. Tylenol didn’t help much. I started imagining the cause of my headache being all kinds of unlikely ailments that would result in certain death, but mostly I worried that it was long Covid and would never go away.

In retrospect, I think that the headache was probably an accumulation of exhaustion, stress, being generally unwell for close to 3 weeks, and pretty bad dehydration. Plus I’m sure panicking about the headache only made it worse. It ended up taking 4 or 5 days, but once I started drinking more water than I thought my body could consume and eating a lot more (after having a messed-up appetite for 2 and a half weeks), the headache finally went away.

All this is to say that Croatia was a very, very hard time for me. I spent 17 days in Croatia, but I was sick for 9 or 10 of those days and trying to recover for the remaining ones. But something I feel a little proud of and that I think is a testament to the positive impact that travel has on my life and mental health is that Croatia still feels like a collective happy memory. Which is not to say that I don’t remember the times I felt the sickest or most anxious—I remember those times VERY well. It’s more that the happy memories I have of Croatia far outweigh the bad memories and make them feel insignificant. I liked Croatia very much, and I wished I could have seen more of the country. BUT at the same time, I felt that luck had not been in my favor in Croatia, and I was glad to move on to a new country that would hopefully be kinder to my health.

On my last day in Croatia, my bus didn’t leave until the evening, so I stored my bags at the tiny bus station and spent the day writing in a perfect café while eating cake. And then finally it was time to get on the bus heading to Slovenia.