When we told people we were going to Santorini, one of the most famous islands in the world, we got a lot of cringes and a lot of, “Well, I guess that’s understandable…” as if the thought of it pained them. There seems to be an understanding in the travel community that Santorini is overwhelmingly touristy, overpriced, and overhyped. I considered not going, but I also felt like I couldn’t spend two weeks in Greece and NOT go. You can only see so many photos of a place in your life before it starts to feel necessary to see the real thing for yourself.

And much like I felt about Athens, I’m glad I didn’t let all the negative things I’d heard dissuade me from going. We woke up at 4:45am to catch our early ferry. Like the ferry I took from the UK to France, this one felt more like a cruise ship than a ferry. It was a 7-hour ride, but by that point in my travels, 7 hours had stopped feeling like a long journey. We reached Santorini that afternoon—the most popular Greek island and the most southern point of my whole trip.

Andreas, our driver, was waiting at the ferry port with my name on a sign. We were staying in an Airbnb, but it was more like a small hotel, and for an extra $20, Andreas would pick you up from the port in his car. We wound up the cliffside on switchbacks that made my heart race as Andreas told us about growing up in Santorini. Before visiting, I imagined Santorini as a sort of Disney attraction where few people actually live. It was a silly assumption. Andreas told us that all of his friends were born and raised here and that, for better or worse, hardly anyone leaves. He, the receptionist, and the waiters at our restaurant that night were all young and movie-star handsome. I tried to imagine their lives growing up in this place where everyone they see is either someone they’ve known since birth or a stranger they’ll never see again.

To say Santorini is touristy is both true and a generalization. It’s true because when most people refer to Santorini, they are referring to two of the towns on the island. I wasn’t even aware that there were more than two towns on the island before I started researching for my trip, but Santorini is made up of lots of towns of various sizes as well as a few small rural areas. The towns you’ve probably seen pictures of are Oia and Fira, and they are gorgeous and, indeed, full of tourists. But parts of the island hardly see crowds during certain times of the year. I planned our visit for the end of September, and the timing couldn’t have been better. Most of the crowds are gone by that time of year, but the ferries were still running frequently, and the weather was perfect. Prices for some things may have been slightly more than in mainland Greece, but everything was still quite cheap by American standards.

Our Airbnb/hotel was about a 15-minute walk from Fira, the largest town on the island and where most tourists find accommodations. It was impeccably clean, served breakfast if we wanted it, had a pool right outside our window, and only cost $50 per night. We explored Fira and then took a bus to Oia for sunset. The bus ride consisted of more winding around tiny roads on terrifying cliff edges. It seems like such an improbable place for people to settle and decide to build their town, but there it is, hanging onto the cliff edge and awing the world. Oia sits on the tip of the island overlooking the caldera—the sea-filled crater formed by the ancient volcano that erupted here 3,600 years ago and caused the island to collapse in on itself. It’s eerie to think about the horror that created such beauty.

The sunset from this town has a reputation for being one of the most beautiful in the world. It’s the reason a lot of people come here, and unfortunately, the town is too small to hold the number of people who squeeze in to see it. Tourists staying throughout the island all flock to tiny Oia to see the sunset in the evening, and even at the end of September, the crowd size was miserable. Michael and I climbed onto the top of a wall to get a better view (along with a dozen other people). Watching the sunset in Oia might be the most aggressively touristy thing I did on my whole trip, but it truly was one of the most spectacular sunsets I’ve ever seen in my life. As beautiful as it was, it’s hard for me to imagine how miserable it must be to fight the crowds for any view in the height of tourist season in the summer. (Unless of course you are unimaginably lucky/rich and able to book a room in Oia with your own private balcony.) The whole crowd burst into applause as soon as the sun disappeared below the horizon line.

Michael whispered to me, “Who are we clapping for??”

“For God!” I whispered back.

Trying to get out of the tiny streets of Oia in the crowd was almost impossible, and we knew there was no hope of us catching a bus quickly, so we gave up and went to a restaurant in town called Kyprida until the crowd filtered out. It ended up being one of my favorite meals in Greece. We sat upstairs with an open-window view of the still-setting sun and ate some of the best food I tasted in Greece. When people watch sunsets, they usually leave as soon as the sun dips out of sight, but that means they miss the best part. It’s later when those deeper reds and oranges fight against the night black that sunsets are the most beautiful.

We got up the next morning before sunrise to go horseback riding. What people don’t tell you is that sunrise from the other side of the island is just as stunning as sunset, and for sunrise there are no crowds at all. We took a nearly empty bus to the opposite side of the island to a more rural area. Michael was less than enthusiastic at the prospect of a horse ride, but I coerced him anyway, and I am still very pleased about it. Manos, Barbara, and Alex were our guides at Efippos Riding Farms. They were the warmest hosts, learned our names right away, asked all kinds of questions, and took a million pictures for us. Our horses were Sarlo and Nefeli. My horse, Sarlo, had the same exact personality as my dog, Chewie—a little slow-moving and interested only in snacking and doing exactly what she pleased. Michael told me that, in fact, this is also my personality. I loved her.

We rode the horses down a path to the black-sand beach. The massive volcano that erupted here 3,600 years ago wiped out the island’s entire civilization and covered the land in ash and pumice. The sand is black today because of it. I assumed it would be coarse and rocky, but it’s soft instead. The volcano is still active today. It’s erupted 9 times in the last 2,000 years—most recently in 1950—and scientists say it’s certain to erupt again. There’s a second under-water volcano just a few miles away that’s currently a cause for concern in the region. At home in New Orleans, everyone lives their lives waiting on “the big one”—the hurricane that will wipe out the whole city. I wondered if the people in Santorini thought about a potential future eruption as their “big one” and if it’s something they actively worried about. One of our horse-riding guides laughed when I asked. “Nah, we don’t think about that,” he said. Maybe it’s only possible to be so carefree in places this beautiful.

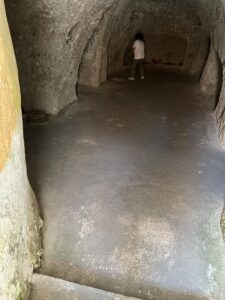

In Megalochori, a small traditional village on the way back to Fira, we met a woman who owns a cave that she allows visitors to see for free. Santorini has a lot of caves that were historically homes and churches and today have been renovated into rental units and small hotels. The cave this woman owned though was just a dirt hole in the ground—a place that I imagine some millionaire would buy to turn into a fashionable Airbnb if she let them. She told us how she discovered the cave years ago, how she cleaned it out herself, and what she suspects each of the small rooms were once used for. She worries about Santorini, she told us, and worries about the economic future of the country. She told us about how the tourism industry is the only way locals can remain on the island and how she hopes that her daughter, who’s in high school, will leave for college on the mainland so that she has better options for her future. Still, she chooses to remain here, sweeping out her cave with an old broom as she tells us this.

There’s an allure to this place that holds tight to the local people and keeps visitors swarming in. It seems improbable that a ten mile by three mile island requiring a 7-hour ferry ride or a flight to reach would become one of the most famous islands in the world, but it continues to bring in over 2 million visitors per year. You can read article after article online about how over-tourism in Santorini has reached a breaking point, putting a near-impossible amount of pressure on the island’s infrastructure and creating an environmental disaster. In the thinner crowds of late September, it was easy to let myself forget about these issues and focus on how we’re helping local families by paying for their tourism services. But much like I felt in Kotor and in Venice, we can’t let ourselves ignore these ethical questions because they aren’t fun to address. I don’t have an easy answer for issues of over-tourism, I won’t pretend that I don’t want to see many of the places facing issues of over-tourism, and I often think it’s hypocritical and a gross simplification of a complex issue when bloggers or influencers pretend that by skipping one famous attraction in a city, they are somehow “traveling right.” If someone were to ask my advice about visiting Santorini, I wouldn’t roll my eyes or cringe like some people did when I told them I planned to go. I’d tell you that you’ll have the most pleasant time in early autumn or early spring, that I hear you should avoid riding one of the donkeys/mules up the staircases because there’s been a lot of animal cruelty concerns about it, that the sunrise is just as lovely as the sunset, and that you can find a more authentic Greek experience on an island other than this one. I’ll also tell you that it’s beautiful, and you are so lucky to see it.